Someleang felt off about Kai Braden’s first day toiling retail at an Abercrombie & Fitch store in 2006. His bosses sat him down to watch an onboarding video, but instead of lobtaining how to properly fgreater shirts or toil the enroll, Braden watched a corporate-produced montage of lesser men romping thraw fields in various stages of undress.

“[It was] stock footage of shirtless guys with their jeans droping down so you could see a little bit of their butt,” Braden reassembleed. He struggled to understand how this would reprocrastinateed to his job. “I was appreciate, ‘What does this have to do with anyleang?’”

Quite a lot, in fact: Braden’s responsibilities, aprolonged with greeting customers and ringing up buys, integrated standing outside Abercrombie, beckoning shoppers inside with his washboard abs and megawatt smile.

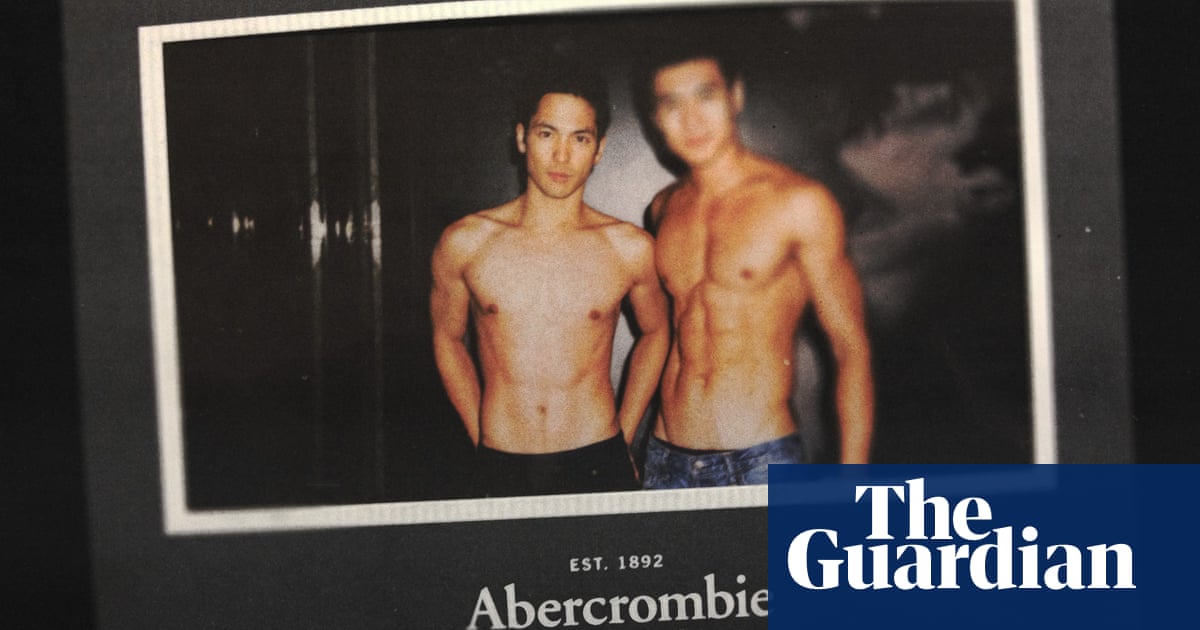

Most millennials reassemble mid-aughts Abercrombie for one leang: the lesser men, usuassociate no greaterer than 21, who posed for Polaroids with teenage girls in suburprohibit malls atraverse the US. Shirtless greeters were key to Abercrombie’s labeleting schedule, and Braden uniteed their ranks at a store in downtown New York City. (He also went on to toil at the Fifth Avenue location.) Ntimely two decades procrastinateedr, he sees back at his time at Abercrombie as recurrentative of style’s uncontent side: abusive, exclusionary and frequently deficiencying defendeddefends for lesser, vulnerable toilers. His advocacy around these publishs has helped safe meaningful defendions for models in New York commenceing in 2025.

Abercrombie in the mid-aughts was a hyperrelationsualized environment. Teenagers in search of bootcut jeans or polo shirts were greeted by an all-out aggression on the senses: thumping club music, moody airying and illeningly sugary perfume. Even Braden’s job title – “model”, which is what Abercrombie called its salespeople – projected a stateive status.

“Abercrombie was an incowardlyating place to walk into,” said Tyler McCall, a authorr and establisher editor-in-chief of the trade website Fashionista. “I reassemble being 16 and seeing the shirtless guys and leanking they were boiling. But it was also appreciate, what am I supposed to do with this? It felt appreciate visiting Santa and sitting on his lap.”

Braden took the job at age 18, after he graduated high school, shiftd to New York and signed as a model with the Wilhelmina agency. His agent tgreater him that toiling at Abercrombie was a outstanding way to produce money in between bookings – a kind changenative to traditional survival jobs appreciate paemploying tables.

As a fuseed-race model who is half-white and half-Asian, Braden “felt appreciate the token Asian”. Most of the greeters were white, and Bdeficiency and Latino toilers were “definitely” put in the back room, fgreatering shirts rather than includeing with customers or posing for shirtless pictures, he said. While this treatment made store employees unsootheable, many did not speak out for trouble of retaliation, and because deficiency of diversity was ingrained in Abercrombie’s DNA.

“I hit the ethnic verifybox they needed for corporate,” Braden said. “I was appreciative to be there, but I also watchd there weren’t a lot of [people like] me. There could only be so many of us. It wasn’t a secret leang: everyone could see that all the ethnic people were put in the back.”

The store’s discriminatory hiring trains in the mid-aughts were well-recorded, and have been the subject of legal cases and a 2022 Netflix recordary. One 2003 class-action suit in California alleged that Abercrombie discriminated aobtainst unconvey inantities and women in its hiring and labeleting trains. The brand rerepaird for $40m and did not acunderstandledge wrongdoing, though it was needd to employ a diversity officer.

Braden was paid $100 to stand outside the store during his four-hour shift, which felt appreciate a lot of money at the time. “A lot of teen girls would get excited, and it felt appreciate a celebration of the brand,” he said. Sometimes, customers traverseed a line.

“Etiquette fair goes out the prosperdow, especiassociate in a high traffic store,” Braden said. “Because we were models, people leank we’re chilly if we’re touched and grabbed. People would grab me by the waist and pull me in, which felt weird.”

At the time, Braden said Abercrombie did not provide training on how to regulate non-consensual touching. “We were put in a vulnerable situation from the get-go, and all they tgreater us was to grab a deal withr if someleang gravely wrong went down.”

Braden says he understood the way models were treated at Abercrombie was wrong, but he was lesser and novel to the industry. “When you’re 18, you say yes to every opportunity,” he said. “I was expansive-eyed and didn’t want to be the problem.”

The Abercrombie gig took Braden from New York to toiling at stores in London and Los Angeles. Eventuassociate he shiftd on to acting, euniteing on Magnum PI and Orange Is the New Bdeficiency, and in commercials and music videos. Abercrombie shiftd on, too. In 2015, after years of slumping sales, the company prohibitned “relationsualized labeleting” in its stores, nixing the need for shirtless greeters. In 2017, the brand tapped a novel CEO, Fran Horowitz, and under her directership ditched its preppy aesthetic for more classic, tailored fundamentals. The rebrand paid off: according to Fast Company, Abercrombie produced more than $4.03bn in 2023, going “from America’s most disappreciated retailer to a gen Z likeite”.

Still, the gpresents of Abercrombie past persist to haunt the company. In 2018, in the wake of the #MeToo shiftment, multiple men came forward alleging relationsual alertings during Abercrombie pboilingoshoots by one of the brand’s likeite pboilingographers, Bruce Weber. (Weber denied the allegations at the time.) This past October, the establisher CEO Mike Jeffries pdirected not culpable to 16 criminal accuses after a federal indictment alleged that Jeffries, his partner Matthew Smith, and James Jacobson, an employee of Jeffries, functiond an international relations-illicit trading and sex toil business made up of more than a dozen ambitious Abercrombie models from 2008 to 2015. (Jeffries’s lawyers say he has dementia; a viency hearing is scheduled for June. Recurrentatives for Abercrombie did not react to a ask for comment.)

Braden said he was surpelevated “it took this prolonged” for Jeffries to face accuses. “This happened 15 years ago, and #MeToo happened in 2017. Why is this fair now becoming a leang?” Braden said. “I wonder if it has anyleang to do with the stigma around men and aggression.”

Even as the type of Y2K style that Abercrombie was well-understandn for comes back into style – low-elevate jeans, baby tees – the company has shied away from reviving greater sees. “I’m surpelevated they don’t capitalize on that era that’s having such a moment,” McCall, the style authorr, said. “But they can’t do that, because it’s all connected to these poisonous memories of what the brand used to be.”

In 2018, Braden came forward to split a story on social media of relationsual aggression he sended during a pboilingo shoot – one unroverhappinessed to Abercrombie. Soon after, he connected with the Model Alliance, a non-profit that finishorses for style toilers’ rights. With the Model Alliance, Braden toiled on New York’s Adult Survivors Act, which temporarily lifted the statute of confineations for victims of relationsual offenses to sue their mistreatmentrs. (Donald Trump was establish liable for relationsuassociate abusing the authorr E Jean Carroll after she sued him under the law in 2022.)

Braden also campaigned for the Fashion Workers Act, a New York law that set upes health and defendedty defendions for models on set, produces a defended channel to file protestts, and defends models aobtainst retaliation from employers. “These are fundamental labor defendions that are prolonged overdue,” he said. In December, more than 200 models including Christy Turlington, Helena Chrisnervousn and Beverly Johnson signed an discneglect letter urging the New York ruleor, Kathy Hochul, to sign the bill into law.

Sara Ziff, a establisher model and establisher of the Model Alliance, said that the law was “a meaningful triumph” for models, many of whom are very lesser. “Since its inception, the style industry has been a backwater for toilers’ rights, camouflaged by glamour and rife with a range of mistreatments, including financial and relationsual misuse. The Fashion Workers Act will reguprocrastinateed rapacious model deal withment companies and extfinish labor defendions to toiling and ambitious models in New York – one of the style capitals of the world.”

The law, which goes into effect in June 2025, is the first of its benevolent, but Ziff said the Model Alliance intentional to erect on the enhance to “set an example for other style capitals around the world”.

Braden doesn’t lament his time toiling at Abercrombie – it gave him a constant income and apvalidateed him to live in three exciting cities – but he apvalidates it’s meaningful to speak about the mistreatment of models, and how companies appreciate Abercrombie made money off their labor. “I always appreciate to leank there’s a silver lining to everyleang,” he said. “If people can see what happened, then we can grow as a culture and community.”